On September 24, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump told a crowd in Georgia that “tariff” is “one of the most beautiful words I’ve ever heard.” The former president’s affection for taxing goods Americans import is well established. But it seems that as we’ve moved closer to election day, his tariff zeal has intensified. Last week, he said he would use tariffs to lower food prices, a suggestion my colleagues Scott Lincicome and Sophia Bagley have labeled “deranged.”

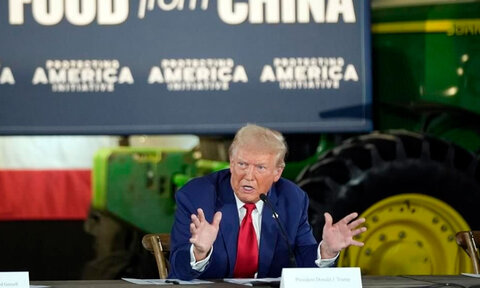

On the twenty-fourth, he threatened a 200 percent tariff on John Deere tractor imports because the company had previously announced plans to shift some production from Iowa to Mexico. This apparently was an off-the-cuff proposal, prompted by the sight of a John Deere tractor behind him at a campaign event in Pennsylvania. He also repeated a threat to automakers that, “We’re going to put big tariffs on those cars that are coming here [from Mexico] at 100 to 200 percent, and they’re no longer going to be competitive … so you better stay in Michigan.”

Scott’s recent post, “Tariff Myths, Debunked,” is a handy takedown of the protectionist justifications for Trump’s tariff fetish, and Pierre Lemieux further breaks down the economics of tariffs in a new Regulation article, including explaining why the prices of domestic-made goods rise when tariffs are applied. I won’t rehash those arguments here. Instead, I want to say it’s long overdue for Congress to reclaim its constitutional responsibility to “regulate commerce with foreign nations.”

At Monday’s event in Pennsylvania, Trump asserted to a reporter that he could unilaterally impose widespread tariffs without congressional approval. After initially responding blithely that Congress will approve his tariffs, he said, “I don’t need Congress, but they will approve it … I’ll have the right to impose them myself if they don’t.”

Trump’s confidence in his presumed omnipotence stems from his administration’s abuse of Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which allows the president to restrict imports on national security grounds. As a thorough analysis by Scott and Inu Manak explains in detail, this justification is dubious and Trump’s use of it during his 2017–2020 presidency to threaten US allies was decidedly abuse.

There was bipartisan support in the Senate to rein in executive branch overstep on trade policy during Trump’s time in office but, unfortunately, nothing came of it. Maybe that will now change. Last week, Sen. Rand Paul (R‑KY) introduced his No Taxation Without Representation Act on, fittingly, Constitution Day. The bill is relatively simple: The president could only impose a tariff if Congress receives a proposal from the White House explaining the rationale for it, which Congress would then have to approve. It would apply to the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 and would not affect US embargoes.

From Paul’s press release:

The No Taxation Without Representation Act seeks to curb the President’s ability to tax Americans by implementing tariffs without Congressional approval. The bill strengthens our system of checks and balances by requiring Congressional consent for any tariffs that significantly impact American businesses and consumers. By restoring the role of Congress in the taxation process, the bill ensures greater accountability, transparency, and long-term economic stability.

Regardless of whether one supports or opposes tariffs generally, our system of government calls explicitly for balance between the branches. With the two candidates for president taking turns sounding like an authoritarian Santa Claus, Trump’s mounting threats to punish American companies with a wave of his wand exemplifies the need to rein in executive overreach.