A centerpiece of the Trump agenda has been to expand executive power at the expense of Congress. To date, the major check on that agenda has been intervention by the judiciary. That intervention, in turn, has prompted an appreciation for our Constitution, which divides power structurally among the three branches. There is, however, a contrary view—promoted mainly by whoever is occupying the White House at a given time—that the separation of powers has become unbalanced; that the judiciary has become too powerful, and has encroached on key executive functions.

Accordingly, I’m posting this brief review, covering the major powers of the three branches, the structure of the executive branch, our constitutional checks and balances, the legitimacy of judicial review, unease regarding judicial supremacy, objections to nationwide injunctions, and President Trump’s reaction to his perceived mistreatment by the courts. Each of those topics warrants more extensive deliberation and treatment than I include here. This post is intended merely to introduce some of the problems and controversies.

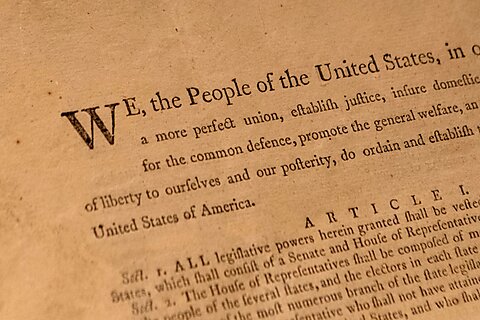

Let’s begin with an overview of the basics.

Powers of the Three Branches

First, the legislative branch: Article I of the Constitution states that all legislative powers are vested in Congress. Section 8 of Article I enumerates those powers. Here are the most important: to levy taxes, pay the debt, provide for the common defense and general welfare, borrow and coin money, regulate commerce, establish rules for naturalization, control the militia, declare war, suppress insurrections and invasions, and make all laws necessary and proper to carry out the other powers.

Second, the executive branch. Article II of the Constitution states that executive power is vested in a single president, who shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed. Section 2 of Article II provides that the president shall serve as commander-in-chief of the army and navy. He can grant pardons and, with Senate consent, make treaties, appoint ambassadors, designate federal judges, and commission all other officers of the United States.

Third, the judiciary: Article III of the Constitution states that the judicial power vests in one Supreme Court and in those lower courts that Congress establishes. Section 2 of Article III extends the judicial power to all cases arising under the Constitution, federal laws, and treaties. Federal courts also have jurisdiction when litigation involves a private party versus the federal government, and one state or its citizens versus another state or its citizens (or versus a foreign state or citizen).

Structure of the Executive Branch

The executive branch comprises fifteen cabinet departments, as well as executive agencies under each department head, and more than 100 so-called independent agencies (excluding numerous sub-agencies). Independent agencies—such as the Federal Reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission, National Labor Relations Board, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation—exist outside the cabinet departments and the Executive Office of the President. Although independent agencies are considered part of the executive branch, they can also legislate—enacting rules and regulations—and some agencies have their own internal courts. The president’s power to dismiss the leadership of independent agencies may be limited.

Checks and Balances

The framers established two key checks and balances: First, the separation of powers. The president can veto legislation and nominate federal judges. Congress can confirm or reject nominees and impeach the president. Federal judges can overturn laws and agency regulations.

The second check is federalism—specifically, the Tenth Amendment, which provides that powers not delegated to the federal government or prohibited to the states are reserved to the states or the people. After the Civil War, federal powers were augmented under the 14th Amendment, which authorized federal intervention whenever a state violates certain constitutionally guaranteed rights.

With that highly condensed recap, let’s examine a few of the issues that have emerged (or become more contentious) as a result of President Trump’s claims to executive preeminence.

Judicial Review of Legislative and Executive Actions

Although the text of the Constitution does not mention judicial review, many state courts already had that power when the federal Constitution was crafted. The Framers plainly intended to establish a government of divided authority. That structural design has become an important interpretive tool for judges when textual references are ambiguous or non-existent. In resolving textual uncertainties, judges will often examine whether a particular act would be congruent with the separation-of-powers doctrine. Judicial review surely qualifies.

A second interpretive tool is the contemporaneous writings of the Framers and ratifiers. In Federalist No. 78, for example, Alexander Hamilton wrote that “a limited constitution … can be preserved in practice no other way than through the medium of courts of justice; whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the constitution void.” He added that the “interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts.” James Madison shared that view: “[I]ndependent tribunals … will be an impenetrable bulwark against every assumption of power in the legislative or executive; they will be naturally led to resist every encroachment upon rights expressly stipulated for in the constitution.” And Chief Justice John Marshall famously wrote in Marbury v Madison (1803): “It is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is.”

Over the years, the Supreme Court has overturned more than 150 acts of Congress and more than 1,200 state and municipal laws, as well as numerous acts of federal and state officials. So, even if judicial review lacks express textual foundation in the Constitution, it is now a fait accompli.

Judicial Finality and Judicial Supremacy

Of course, if you’re a nonstop litigant who often finds himself on the losing side, judicial review can be a problem. That’s the pitch now coming from President Trump, who would prefer that he, and not the judiciary, should have the final word on legal and constitutional disputes. The president, like his predecessors, would relish compliant courts rather than judges who constrain his executive prerogatives. The counter-argument is that notwithstanding the finality of Supreme Court pronouncements, the judiciary is still, as Hamilton asserted, the weakest branch, endowed with “neither force nor will, but merely judgment,” relying on its ability to interpret and persuade.

Even if the judiciary wields provisional supremacy when “say[ing] what the law is,” Congress and the executive can sometimes sidestep court rulings by adopting different procedural means to accomplish valid ends. That may well be the Trump strategy down the road – to elicit legislative support for those executive orders that courts have rejected for want of congressional authorization.

The legislative and executive branches retain control over judicial appointments and impeachment, plus the creation (and extinguishment) of “such inferior Courts as Congress may … establish.” Indeed, the Constitution declares that the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court is subject to “such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.”

Yes, the Supreme Court is final—even if not infallible. And the Court’s finality is buttressed by its independence. Justices are insulated from most political pressures and thus better able to act as a check on the political branches. But there are, I believe, sufficient cross-checks among the co-equal branches to foreclose judicial supremacy.

That said, there are legitimate concerns about the scope of judicial power.

District Judges and Nationwide Injunctions

Can a single district judge issue an injunction that is binding on everyone (not just the parties to a specific case) and everywhere (not just the jurisdiction where the judge presides)? That question has been marinating in the courts for a while, and it’s not yet settled. On May 15, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Trump v. CASA. The primary issue in the case is whether Trump can deny birthright citizenship to the children of illegal aliens. But before addressing that issue, the Court will decide whether to stay nationwide injunctions, issued by three district judges and affirmed by appellate courts, applicable to Trump’s executive order on birthright citizenship. Should the injunctions affect only the individuals, identified organizations, and states that filed the cases?

Opponents of nationwide injunctions have pointed out that a single district judge can effectively overrule multiple judges who already rejected the injunction request. In fact, an injunction from one district judge can have even greater effect than a merits-based decision from an appellate court in another circuit, which binds only courts within that circuit. For those reasons, some legal scholars have proposed the alternative of class actions, which could grant relief to a broad array of plaintiffs. But class certifications can be time-consuming, and have to overcome significant procedural hurdles.

A March 31 bill by Sen. Chuck Grassley (R‑IA) would bar enforcement of injunctions against the executive branch by non-parties to a lawsuit. It would also make temporary restraining orders against the government immediately appealable. The problem with that solution is that some situations require national uniformity. It’s neither practicable nor effective to allow only identified parties within a specific jurisdiction to enforce an injunction against, for example, building a border wall, regulating social media content, or receiving certain mail-order products. Probably a better solution would be for Congress to bar a nationwide injunction issued by a district court unless: (a) it’s needed to fully remediate an injury, or (b) the government has violated clear, controlling Supreme Court precedent, and (c) Congress has provided an expedited appeals process.

Meanwhile, the problem has become more acute: Trump has been enjoined more than 100 times, versus 24 for George W. Bush, 38 for Obama, and 28 for Biden.

Trump’s Reactions to Judicial Decisions

In response to the barrage of injunctions against him, Trump has called for the impeachment of federal judges. He’s called them “lunatics,” guilty of “sedition and treason.” Trump’s allies in Congress have filed articles of impeachment against several judges. Speaker Mike Johnson threatened to eliminate or defund offending judicial districts. Stephen Miller warns of “naked judicial tyranny.” J.D. Vance stated, “Judges aren’t allowed to control the executive’s legitimate power”—obviously begging the question of what’s legitimate. Those reactions are provocative, misguided, and dangerous.

After the Court of International Trade gutted most of Trump’s tariffs, he vented his frustration on the Federalist Society, the influential group of conservative and libertarian lawyers that had been instrumental in selecting Trump’s judicial nominees. Despite successful Court picks, Trump now gripes that he got bad advice from Leonard Leo, a Federalist Society director who, according to Trump is a “sleazebag” and “probably hates America.” More likely, what actually vexed Trump is that federal judges, unlike his sycophants in Congress, have been allegiant to the rule of law when the president misbehaves. On the record, Republican-appointed district judges have ruled against Trump 72 percent of the time—nearly as often as the 80 percent loss rate from Democratic-appointed judges (according to a May report from Stanford University).

Most regrettably, Trump is apparently planning to take out his exasperation by appointing to the bench political hacks who commit to rule in his favor. If he implements that policy, our concern will be with executive supremacy, not judicial supremacy. Any relief afforded by our constitutional separation of powers will depend upon the emergence of a congressional backbone.